Café Tacuba, a 100-year-old restaurant in downtown Mexico City and our first stop whenever my family visits the city, is as much national metaphor as a place to eat.

The restaurant is a veritable shrine to mestizaje, the fusion of Indian and Iberian that produced the Mexican culture. As food writer Raymond Sokolov has pointed out, it is Mexico, with its complete mixing of cultures and people that is the true “melting pot,” the USA being more of a tossed salad of distinct ingredients. There is hardly a dish on the Tacuba menu that does not make use of New and Old World ingredients, scarcely a person in the room who does not combine in his genetic make-up something of the two cultures. This hybridization evokes both tremendous national pride and persistent denial, both of which are on view in the restaurant, too.

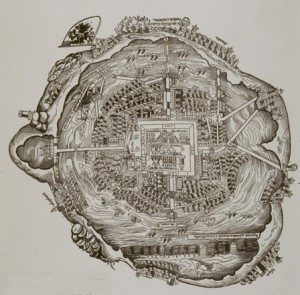

The city in 1519: Tacuba’s location is to the left of center, possibly within the temple compound walls.

Café Tacuba is located in the very heart of this Spanish colonial city built on the ruins of the Aztec capital, the most glorious city in the Western hemisphere at the time of Cortes’ arrival.

Early or late, it is packed with diners downing coffee and cakes or hearty enchiladas, chilaquiles, tamales, the very antipode of nouvelle cuisine. The servers—motherly women, dressed like Victorian nannies—rush from table to table. Alcohol isn’t served, and the gaiety is sustained without it. Instead, the patrons drink fruit juices, hot chocolate, or coffee in many forms, including a condensed syrup that sits in a cruet on each table like a condiment and is poured into tall glasses of hot milk. For a century, Mexicans have been coming here to savor the delicious food along with their cultural patrimony.

We wend our way through the romancing couples of varying ages, the trios of elegant women, the families and businessmen and occasional foreigners or bohemian ex-pats, all gesticulating between bites, engrossed in conversation. We don’t need the menu; our first meal here is always the same: huge flat, corn-husk wrapped tamales, quesadillas, and enchiladas de mole, my husband’s favorite.

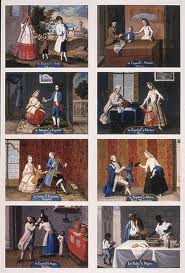

Meanwhile, on the back wall, hanging over this scene and peculiarly disconnected from it, is another gustatory drama—a painted one—in which the silent, impassive life-sized figures are as involved with eating as the real life diners below. The mural is not fine art, but the story it tells and, even more, the stories it omits, reflect the conflicted feelings Mexicans tend to have about their hybrid civilization and its legacy.

This painting, a triptych, purports to be a testimonial to cultural fusion. It recounts the history of chocolate, and, by extension, the Spanish debt to the indigenous people of Mexico. In the left-hand panel, a lovely Indian woman is bringing the traditional chocolate drink to its proper froth, rolling a wooden swizzle-stick between her palms, while two Indian men drink from reverently cupped wooden bowls. In extreme contrast, in the right-hand panel, two aristocratic young Spanish ladies in a baroque salon delicately select chocolates from a silver dish. The two worlds come together in the large central panel. A gentleman in wig and ribbons and a bald, homely priest have joined the ladies, one of whom is passing a glass of chocolate, while an Indian server waits in the background with a pitcher of the precious brew on a tray.

This painting, a triptych, purports to be a testimonial to cultural fusion. It recounts the history of chocolate, and, by extension, the Spanish debt to the indigenous people of Mexico. In the left-hand panel, a lovely Indian woman is bringing the traditional chocolate drink to its proper froth, rolling a wooden swizzle-stick between her palms, while two Indian men drink from reverently cupped wooden bowls. In extreme contrast, in the right-hand panel, two aristocratic young Spanish ladies in a baroque salon delicately select chocolates from a silver dish. The two worlds come together in the large central panel. A gentleman in wig and ribbons and a bald, homely priest have joined the ladies, one of whom is passing a glass of chocolate, while an Indian server waits in the background with a pitcher of the precious brew on a tray.

The illustrated story is that of the Spanish appropriation of the Mexican Indian’s treasure: chocolate. It was the Mayan ambrosia, literally the gods’ food, eaten on ceremonial and religious occasions by mere mortals after the gods had had their fill. Because the Spanish systematically destroyed all scientific as well as religious Mayan writing, little is known about their cultivation of chocolate, only that they roasted the seed of the cacao pod, ground them, then mixed the resulting powder with water, chili, musk, and honey, whisking the boiling liquid with a wooden implement.

One of the few extant Mayan texts lists chocolate as among the riches paid in tribute to the Aztec king, Moctezuma, who apparently had developed a passion for it. Two thousand jars a day were supposedly consumed in his household. When Cortes arrive in 1519 and was greeted by the frightened king who mistook him for the returning god Quetzalcoatl, he asked for treasure and was shown heaps of ground cocoa. So highly valued was the stuff that until the 18th century the seeds, bagged in standard quantities, were used as money. Although initially unimpressed with the bitter brew, Cortes and his men quickly came to appreciate its intoxicating and supposedly aphrodisiac qualities. Perhaps the pomp and ceremony with which it was served helped them to overlook its bitter taste: following an elaborate ceremony celebrating the cacao harvest—complete with human sacrifice, masked dancing and erotic games—it was offered to them in golden cups by naked virgins.

Freely mixing the exotic chocolate with their own ingredients, the Spanish made something new and original. High-born nuns quickly solved the problem of the drink’s bitterness in a convent kitchen—as fertile a source of culinary inventions in the New World as in the Old—with local vanilla, sugar from the East, and cream from European dairy cattle substituting for the traditional spices. Chocolate became an overnight sensation as soon as the first cargo ship reached Spain, and during the 16th and early 17th centuries, it was the number one Mexican export. Spanish ladies developed such a passion for it that they drank it from morning to night, even having it served to them in church. The new and improved version of the Mayan drink of the gods was profitably controlled by the Catholic Church, whose popes and bishops became embroiled in weighty ecclesiastic debates as to whether drinking it should or shouldn’t count as breaking a religious fast. Fortunes were made and souls were sold in the greedy pursuit of profit from a European food fad.

The Tacuba painting celebrates the cultural benefits of cross-fertilization but as a circumscribed event, with the races leading parallel lives. This was the Spanish conquerors’ ideal, their original vision of two separate nations—the colonial and the native—that quickly proved untenable. In fact, with the shortage of women on the first boats, racial mixing began almost as soon as the Spanish soldiers stepped ashore. In contrast to the white population’s isolation of native Indians in the USA and Canada, the Spanish continuously interbred with the indigenous population and created a new, metizo race.

This racial blend was further complicated when the Spanish began importing African slaves, in response to the Indians’ staggering mortality rate. The long, brutal voyage and concomitant loss of life, made the imported slaves expensive, in comparison with the freely available, if less hardy Indians, and the practice was soon abandoned, but not before over one hundred thousand Africans had joined the Mexican population.

Diego Rivera portrays the creation of Mexico’s mixed race symbolically in his great stairwell mural in the National Palace: a Spanish soldier raping an Indian girl. The muralist of the Café Tacuba, no social revolutionary, keeps his handsome Indians safely in a frame of their own or in the background of the central panel, the suitably meek servant.

The cross-fertilization—readily accepted as enrichment in the kitchen—was thought of quite differently in the sexual arena. As the progeny of these predominantly out-of-wedlock couplings muddled the social and political hierarchy, racial mixing became cause for alarm. Initially these children were treated as a public embarrassment or worse, sometimes abandoned by all the races to roam the streets homeless and pitiable. Later, as their numbers increased a cast system evolved which defined all aspects of social, political, and economic life. Racial genealogy became a national obsession.

These sets of paintings, called castas, were commissioned by New World-born Spaniards to codify racial categories resulting from interbreeding. By the end of the colonial period in 1821, one hundred categories of possible mixed races were defined.

Initially, the Spanish-born tenaciously maintained their superior position by distinguishing themselves even from Mexican-born Spanish, known as creoles, contending that the climate and the milk of their Indian nursemaids were sufficient to contaminate the creole character. Between the Spanish-born, “almost white” at the top and the Indian at the bottom, the system recognized, in addition to creole, mestizo and black: mulatto (off-spring of black and white), zambo (of Indian and black), morisco (of mulatto and white) and castizo (mestizo and white). Those at the bottom of the social ladder endured dismal lives, deprived of most rights and all opportunity.

In the Tacuba painting, however, there is no suffering. The Indians in the mural, though somber, look like movie stars—the woman shapely, the men muscular and handsome. They are well dressed in costumes that seem to have come straight from the wardrobe room. None of the figures expresses any emotion. If the Indians are resentful, they are keeping it to themselves. They are depicted as a proud, noble people (and unbelievably robust in the light of their historic suffering). Moreover, although there is no room for them at the table, the painter has made sure to point out the one place in which they have clearly benefited from the cultural exchange: the kitchen, where they have acquired sugar, a large bowl of which sits on the floor of the Indian hut. The Spanish, meanwhile, are depicted as equally handsome and without malevolence. While Diego Rivera and the other muralists generally depicted the ruling class as brutal and vicious, the priests as licentious and rapacious, the worst one can say about the Spaniards portrayed in the Tacuba mural is that they are oblivious to the Indians and to the enormous disparity of wealth and position between their two societies.

In reality, however, when the Spanish conquered Mexico, they began centuries of abuse. Although perhaps no more brutal than that of the blood-obsessed Aztecs, theirs had a much more devastating effect. Enslavement, theft of land, debasement to subhuman status, and exposure to imported disease took an extraordinary toll; in the first one hundred years under the Spanish, the Indian population was reduced by at least 90%. Centuries of political change have done little to improve the Indian’s plight. Neither the 1810 War of Independence, which freed Mexico from the Spanish and created a creole and mestizo ruling class, nor the 1919 Revolution, which ended the Diaz dictatorship and established the modern Mexican constitution, restored the Indians’ land, lifted them from poverty, or freed them from discrimination. The enormous debt, idealized in the mural, remains unpaid. The painting is a fiction—people, after all, do not come to a restaurant for consciousness-raising. For all its musty historicism though, the painting, with its racist underpinnings and denial of a conquered people’s denigration, remains timely. If the Tacuba’s appeal hasn’t changed in a hundred years, neither has the dark side of Mexico’s cultural pride. Of course, we in the USA are just as inclined to romanticize our own embattled Native Americans; the difference is only that few of us can claim them as forbears.

Mexico has seen great upheavals since the early years of the Revolution when the Café Tabuba opened, but inside the restaurant’s double-swinging doors—as inside the national psyche—not much has changed. How do prosperous Mexicans reconcile their anti-Indian feelings with the knowledge that the victims are their own genetic relations? Perhaps they tell themselves that it is class and not ethnicity that is at issue, but can the two really be separated? If the modern diners looked up to consider for a moment the figures in the painting, would they think of both the Indians and the Spaniards as equally their ancestors?

But no one does look up; no one notices the murals at all. Eventually the server arrives with our order: tamales of rough, grainy, New World corn meal, wrapped around bits of darkly roasted Old World pork; quesadillas of tender, blistered Indian tortillas oozing with molten white cheese from Spanish dairy cows; and enchiladas de mole, an addictive dish invented by an ingenious nun who mixed local chocolate and chilies with imported cinnamon and coriander. We pour the rich, dark coffee syrup into our tall glasses of shimmering hot milk and watch the colors swirl together, mingle, and, in an instant, blend.

first published as "Cafe Tacuba," in Travelers' Tales: Food— A Taste of the Road, O"Reilly and Associates, San Francisco, CA, 1996.

Leave a Reply