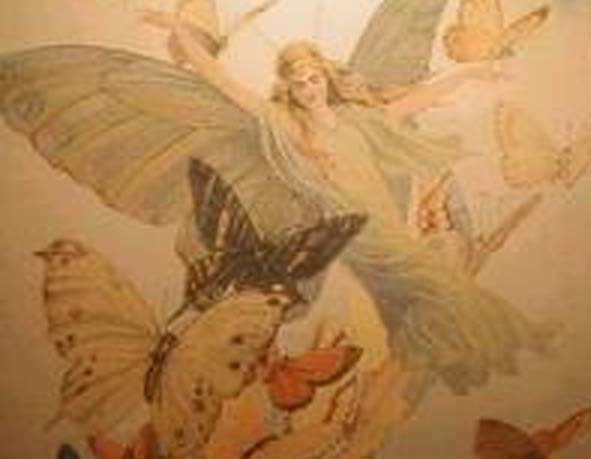

Whether it is their metamorphosis, their vibrant colors, their gentle fluttering, their beauty, something about butterflies touches our imaginations. They transcend our negative associations about insects and seem more fairies than bugs. Perhaps this accounts for the great variety of names for butterfly in different languages.

The “monarch” was named by a 19th century American entomologist, Samuel Scudder, because, according to some, “it is one of the largest of our butterflies, and rules a vast domain.” Others claim he chose the name to honor the English king William III but failed to explain why an American would be so inclined.

The derivation of the word ‘butterfly’ is more mysterious, and there is debate about how butter got into it. The most commonly posited is that it comes from the insect’s depiction in folk traditions, according to which is the notion that butterflies (or witches in their form) steal butter:

This explanation seems to be corroborated by the German word for the insect, schmetterling, which comes from schmetten, meaning cream, and may be a translation from the Czech, svetena. Butterflies have also been called in German “milk thief” or “butter bird.” What is strange is that entomologists can make no sense of the butter connection at all. An even more curious explanation is that the insect’s feces is yellow, when in fact butterflies leave no feces.

Does this interesting, 2008 webpost from Eugene Volokh shred light on the issue?

“If you read (and who doesn’t?) R. B. Onians, The Origins of European Thought about the Body, the Mind, the Soul, the World, Time, and Fate (Cambridge, 1951), you will learn more than you probably want to know about how the ancient Greeks thought brain matter, spinal fluid, marrow, and semen were essentially the same thing, the very stuff of life, the fluid that makes the difference between a dried-up corpse and a moist live human. Add M. Davies and J. Kathirithamby, The Greek Insects (Oxford, 1986), pp. 104-7, and you will find that the butterfly was called psyche, ‘soul’, because it was thought to be or somehow represent the soul of a dead human. The illustrations on pp. 104-5 of the latter book depict ejaculating phalli (one of a herm, the other of a flute-player) with butterflies floating above the stream. As D and K note (106), “The juxtaposition of semen and butterfly may also remind us that some modern European names for this insect similarly connect it with liquid vel sim. that possesses nutritive power (English butter-fly, German Molkendieb (whey-thief) etc.).” … In one of William Blake’s illustrations to his Songs of Innocence and Experience we see ‘The organ of generation . . . with the generative principle breaking from its crest in the form of tiny winged . . . figures’ (G. Keynes in his edition (Oxford 1970) on pl. 11).”

Many of the derivations below are thanks to Matthew Rabuzzi Cupertino via the Cultural Entomology Digest. The variety of names and derivations is enormous, but it is possible to sort them into some helpful groupings.

Several languages relate the butterfly to the soul (or the stuff of life, as in the Volokh post above). The Ancient Mayans thought the returning Monarchs were the returning souls of the dead, so there seems to be something to this that spans culture:

Greek: psyche, meaning both “soul” and “breath”

Latin: papilio, also associated with the soul of the dead. And from the Latin:

French: papillion

Catalan: papallon

Old High German: fifaltra, the p shifting to an f

Anglo-Saxon: fifoldara

Old English: fifalde

Old Norse: fifrildi and maybe

Italian: farfalla and maybe

Irish: feileacan

Swedish: fjäril

Icelandic: fiðrildi

Russian dialect: dushichka, from “duska,” the soul

In other languages, the derivation seems to be original to that language, often deriving from folk culture:

German: schmetterling, from the word schmetten, meaning cream and relating to the butter in butterfly

Norwegian: sommerfugl, meaning summerfly (or summerbird? vogel being German for bird)Norwegian: sommerfugl, meaning summerfly (or summerbird? vogel being German for bird)

Portuguese: borboleta, either from the Latin or from “bellus,” meaning beautiful

Russian: babochka, a diminutive of baba or babka (old woman or grandmother and, by extension, witch).

Scottish Gaelic: dealan-dè, literally “God’s electricity”

Spanish: mariposa, from La Santa Maria posa, or the Virgin Mary alights

Yiddish: zomerfeygele, summerbird

Several languages have a word that seems to suggest how butterflies look in flight, a kind of visual onomatopoeia. Since the Latin for “twitter” is pipilo, could some of the Latin derivative words come from this rather than from papilio?:

Albanian: flutur and Romanain: fluturi: meaning something that flutters, with a connotation of uplift

Amharic (principal Ethiopian language): bira biro,” meaning restlessly flying insect

Arabic: bu frtutu, buu meaning, having the attribute, and frTuuTuu, the onomatopoeia for ‘flutter.’

Dagon: pee plim

Hebrew: parpar

Hindi: titli

Iranian: pir pir, floating in the wind

Japanese: choochoo

Javanese: Kupu

Kwara’aw: bebe

Lan: fufu

Maori: pepe, probably onomatopoeia for the darting, erratic nature of the butterfly’s flight

Mekeo (South East Papua): fefe, fefe-fefe

Mekeo (South West Papua): pepeo

Senegalese: lupe lupe

Tshiluba (Zaire): bulubulu

Yoruba: labalaba

Zulu: uvevane

In still other languages the word seems to derive from the shape of the insect or from its symmetrical folding:

Modern Greek: petaloudia, related to the words for “petal, “leaf” and “spreading out,” and perhaps derived from “ptero,” wing.

Another German word: tagfalter, perhaps meaning “day-hinge” or “day-folder,” which makes visual sense.

Mandrin: hu-tieh, but from what? As “tieh” means 70, the butterfly has come to suggest longevity, but what is its derivation?

What are the derivations of the names for butterfly in other languages? Can you add to the list?

Leave a Reply