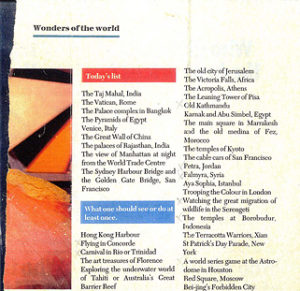

After my mother’s death at 83, I was surprised to find among her personal papers a frayed and folded magazine clipping entitled Wonders of the world. It consisted of two lists: one proclaiming the world’s ten greatest sights and the other hedging with another 25 runner-ups. The clipping was tucked into her pocket date book, a tool as important to her as her right hand. She had torn the list out, marked the places she hadn’t yet seen, and kept it—judging from a date on the back—for almost ten years.

In the midst of my ruminations about my mother’s true identity, the scrap of paper took on the weight of a mysterious relic. Could this really have been important to her? Did it hold clues to her essential self, to some piece of her soul and my inheritance?

It was hard to believe: the list was journalistic trivia, too silly to be taken seriously—and my mother was not a silly woman. In principle, I can understand the appeal of a Wonders of the World list, with its definitive rankings, its distillation of travelers’ options. But, in practice, picking and choosing among the earth’s “wonders” to come up with the ultimate list is inherently subjective, absurd, in fact.

My mother’s version was particularly inane: the Sidney Harbor Bridge beating out the Acropolis for a place in the top ten, Trooping of the Colors on a par with Aya Sophia. “Flying in the Concorde” but not cruising the Nile. Old Katmandu, but not Old Kyoto. The Saint Patrick’s Day Parade but not the Palio. And where was Paris, Machu Pichu, the Alhambra?

Who in the world made up this list? To take it seriously meant granting authority to an anonymous writer of unknown credentials. And my mother was not the sort of person to let others dictate. As the youngest of four daughters, she had responded to her parents’ disappointment at not having a son by jettisoning their expectations and defining herself. She knew what she wanted and went after it: an education and a career. A dress-buyer for a large New York department store, she broke all the records and browbeat anyone who couldn’t keep up. On the job and at home, she was a model of militant determination.

And a ferocious traveler. She had seen all ten of the designated current wonders, plus all but eight of the second-tier list. Compulsively efficient, she had marked the sites not seen—as there were many fewer of them. Had she been using the list to plan itineraries? In all the years she’d carried the clipping she had not erased even one of her eight x’s. Could the list have simply served as a reminder of how much she had already seen?

Either way, it summed up everything about my mothers’ kind of traveling I loved to put down. As I saw it, she turned travel into a form of consumption, a kind of trophy collecting. Worse, by letting the tour companies select the sights, she became a pawn of the tourism industry. In one way, I thought the list was perfect: what drove her around the world wasn’t wanderlust—it was lust for wonders.

But when I looked into the history of the original list of Seven Wonders, I was surprised to find that my mother’s travel m.o. wasn’t new. It could be traced back more than 2000 years to the compiling of the original list in the middle of the third century B.C. when—at least in the Mediterranean world—travel-for-travel’s sake began.

Herodotus, the fifth century B.C. historian, who had traveled widely and written about what he’d seen, had not inspired followers. After the destruction of the Persian fleet in 480 B.C., goods began pouring into Athens from all over the known world, but the idea of venturing out to see the origins of these goods had not occurred. After all, travel was expensive, difficult, and—given the constant fighting among the Greek city-states—life-threatening.

It wasn’t until Alexander conquered and united the Mediterranean world in the third century B.C. that the great beyond suddenly seemed to beckon. Tales of wonders brought back by his army sparked the idea of Seven Great Sights to be seen. Reading or hearing about Herodotus’s travels was suddenly not enough. As more and more people began traveling—diplomats, civil servants, merchants, athletes, philosophers, teachers, doctors, actors, musicians, poets, engineers, architects—everyone suddenly wanted to see the wonders for themselves. And with the possibility of safe travel, a vogue for sightseeing began.

Neither Herodotus’s list of Great Sights—which no doubt began the tradition—nor a 250 B.C. list of Seven Sights survived. The oldest list we have, in the form of a short poem by Antipater of Sidon, the Greek poet, codified what we know as the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World and dates from 150 BC, a time when the wonders had already become tourist destinations. Many competing versions from that era exist, but they were all derivatives of Antipater’s:

1. The Pyramids of Egypt

2. The Temple of Artemis at Ephesus

3. The Hanging Gardens of Babylon

4. The Statue of Zeus at Olympia

5. The Mausoleum at Halicarnassus

6. The Colossus of Rhodes.

7. The Walls of Babylon, later replaced with The Lighthouse of Alexandria

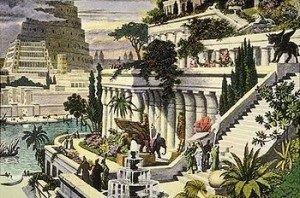

This list of wonders has come down to us as an awe-struck expression of what appears to be almost superhuman achievement. The fabled sights, all man-made and representing a range of construction types—temple, tomb, monumental statue, lighthouse—proudly trumpet human  accomplishment. All were gigantic and/or sumptuous. Phidias’ immense wooden statue of Zeus sat on a gold-plated ebony throne encrusted with semi-precious stones, its beard and clothes covered with gold, the undraped parts with ivory. The terraced Gardens of Babylon were lush with flowering vines and fruit trees, a tropical

accomplishment. All were gigantic and/or sumptuous. Phidias’ immense wooden statue of Zeus sat on a gold-plated ebony throne encrusted with semi-precious stones, its beard and clothes covered with gold, the undraped parts with ivory. The terraced Gardens of Babylon were lush with flowering vines and fruit trees, a tropical  paradise in a barren desert. The Lighthouse of Alexandria was for centuries the tallest building on earth, after the Giza pyramid. Feats of engineering, the Seven Wonders represented man’s triumph over the laws of nature, a stretching of human limits. So huge, so lavish were they that mere description could not suffice: only seeing was believing.

paradise in a barren desert. The Lighthouse of Alexandria was for centuries the tallest building on earth, after the Giza pyramid. Feats of engineering, the Seven Wonders represented man’s triumph over the laws of nature, a stretching of human limits. So huge, so lavish were they that mere description could not suffice: only seeing was believing.

This sense of the marvelous was increased by the fact that there were seven wonders, a number chosen not because of any specific limit to human achievement but because important lists usually numbered seven (as in wise men, deadly sins, and days of creation), the number having conferred a sacred aura since prehistory among the monuments’ builders: the Babylonians, Egyptians, and Greeks. Competing lists varied as to wonders but never as to number. The magic number ‘seven’ rendered a list complete. It marked it as definitive. Conveniently, as far as destinations went, the number was large enough to be a challenge but small enough to be doable in a lifetime.

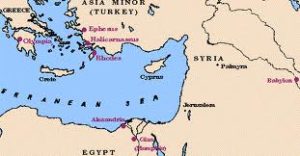

That the list was practical as well as poetical has largely been forgotten, but, in fact, it was used to promote travel. It was a list of must-see sights. And with thriving Greek colonies all over the Mediterranean and ship captains enjoying a new-found profit from the passenger trade, it was clever marketing. Then, as today, transporting, housing, feeding, and guiding travelers was good business. The seven sights were scattered around the Aegean and eastern Mediterranean with only one (the Zeus at Olympia) on the Greek mainland. Two (the Temple of Artemis and tomb of Mausolus) were on the coast of Asia Minor, and the bronze Colossus was just off shore on the island of Rhodes. The Gardens of Babylon were the most remote—a long trip inland from Byblos—but the Pyramids were an easy cruise down the Nile from the port of Alexandria, with its huge, off-shore lighthouse). The list of wonders encouraged travel within the Greek world—feasible travel.

Moreover, it seems to me, the list didn’t merely promote travel, it promoted the particular kind of travel we think of today as tourism. From the first, travelers were focused not on the geography, the culture, the people, the journey itself, but on specific touted sights, sights that were chosen for them and that then spawned commercial enterprise. The word “tourist” wasn’t coined until the 19th century, when Stendhal used it to signify a person on holiday who makes a tour, a programmed circuit; but, nevertheless, it seems that as soon as there was travel for pleasure, there was tourism—of the checklist variety.

Moreover, it seems to me, the list didn’t merely promote travel, it promoted the particular kind of travel we think of today as tourism. From the first, travelers were focused not on the geography, the culture, the people, the journey itself, but on specific touted sights, sights that were chosen for them and that then spawned commercial enterprise. The word “tourist” wasn’t coined until the 19th century, when Stendhal used it to signify a person on holiday who makes a tour, a programmed circuit; but, nevertheless, it seems that as soon as there was travel for pleasure, there was tourism—of the checklist variety.

Eventually, as the Seven Wonders were destroyed or fell into ruin, passing from three-star tourist attraction into myth, the original list of wonders itself became a piece of folklore. From time to time over the centuries, writers produced updated lists, which, incidentally, make an interesting measure of a civilization’s values. A wonders list from 550 A.D., concerned more with spirituality than actuality, struck off the Olympian Zeus and Temple of Artemis as too pagan and replaced them with Noah’s Ark and The Temple of Solomon. By medieval times, East-West trade was expanding European consciousness and the list included the Porcelain Tower of Nankin and the Great Wall of China. An American list compiled in 1946 included Los Alamos, home of the atomic bomb.

The values imbedded in my mother’s particular list, on the other hand, resist definition.

Her list aside, my mother’s character shed light on her traveling style, and vice-versa. “You haven’t lived until you’ve seen the Taj Mahal,” she liked to say, not bragging but intoning authoritatively. My mother subscribed to the metaphor of life as a banquet where you were meant to consume as much and as great a variety as possible. She had season opera seats, and tickets to every hot play and blockbuster museum opening. Living well to her meant packing in as many premium activities as possible. And here I could see that the List’s underlying philosophy would have made sense to her. The List says, “These are things you should do or see before you die. Don’t miss out! Life is short.” It implies that the good life can be measured in a quantity of specific experiences.

In fact, the more I thought about it, the more I could see that the List of Wonders was, in many ways, just my mother’s cup of tea. She was a list devotee. When I sorted through the methodically organized photos of her many trips, I found her characteristic lists: items packed, gifts bought, meals eaten, prices paid. A journal of enumerations.

Perhaps list-making gave her a sense of control over the speeding engine to which she had hitched her wagon, hurtling across the bounds of class and culture, like so many other children of immigrants. It certainly gave her a visceral satisfaction. It was visible, this deep pleasure in imposing order, in her addiction to jigsaw puzzles, which she rented from a shop in mid-town Manhattan, restricting herself, in the interests of economy, to two a week. As a child I used to watch her run her hands over the surface of a just-completed puzzle, sighing, all the hundreds of pieces now perfectly fitted together: the one right solution.

Possibly it never occurred to her to question the list. When she felt confident about her knowledge, she was tyrannically assertive and controlling. But when she ventured outside the boundaries of her own expertise, she could be equally passive and often completely threw away the reins of command: to her decorator, to her hairdresser, even once to a used-car dealer in Mexico. Under all the bravado must have lurked a hidden river of self-doubt. She hadn’t even crossed off the list the World Series game at the Astrodome, an experience she would have paid good money to miss.

It seems, however, that my mother was not alone in passively following a set checklist; people have been doing it for two thousand years. Mass travel—with its guides and guidebooks, inns and taverns, touts and souvenir sellers—goes back to the Romans. By the second century A.D. citizens, both the wealthy and the less so were using their frequent holidays to take in a series of prescribed sights, a tour made easy by a budding hospitality industry. By then, only the Lighthouse of Alexandria and the Pyramids at Giza still survived from the original List of Seven, but there were new additions: a consultation with the oracle at Delphi, guided tours of ancient Athens and the Trojan ruins, and a climb up the Mt. Etna volcano. By the end of the Roman era, all but the pyramids had crumbled and, along with Antipater’s poem, been lost. And yet the idea of the Seven Wonders lived on.

Codified sightseeing never ceased to be the organizing principal of mass travel. Even in medieval times, when travel took the form of religious pilgrimage, the interplay between sightseeing and commerce remained unchanged: sights attracted tourists; tourists and their money supported enterprise; enterprise promoted and created sights to attract more tourists. Thus the new churches going up all over Europe made themselves into major tourist attractions by acquiring holy relics which could then be credited with miraculous cures. Bits and pieces of Sts. Francis, John, and Catherine were popping up all over the Continent—not to mention weathered slivers of the true cross. Pilgrimages became so popular that the Church organized them into the lucrative system of indulgences, or remission of sins, granted in exchange for paid visits. By the 13th and 14th centuries, the pilgrimage circuit was a mass phenomenon for rich and poor alike and, by the 15th century, all-inclusive package tours from Venice to the Holy Lands were available.

During the Renaissance, when wealthy Europeans began traveling for refinement and education, they followed a customary itinerary that had been codified into The Grand Tour—a circuit so popular and profitable for the places visited that cities developed sights in the hope of getting on the list. The scheme worked: a balcony designated as Juliet’s brought the hordes to Verona.

In 1532, a Dutch painter, Maarten Van Heemskerck made the Grand Tour with the plan of seeing and painting the then Seven Wonders. He got as far as Italy—painting the Coliseum and St Peter’s under construction—and was inspired to produce a series of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient world, the poem of Antipater having resurfaced in 1500. The little he gleaned from research he more than compensated for with imagination. Heemskerck brought Italian art back to Holland and fascination with the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World back to life.

By Victorian times, The Grand Tour had become a middle-class activity, Thomas Cook had invented the Tourist Industry, and tourism was assuming its present, familiar shape. The modern whirlwind, packaged tour—with one city standing in for a whole country, a few buildings for an entire civilization—is the ultimate extension of checklist traveling: see the Coliseum and Forum; get the Roman Era.

But such reduction to absurdity only reveals the underlying fallacy that was there from the beginning. The original and subsequent Seven Wonders lists purport to be objective and definitive, but the whole notion of picking and choosing to come up with a precise number of ultimate sights cannot but be arbitrary. Alexander’s Empire certainly contained far more than seven wonders; after all, we remember most of the seven only because they were immortalized in the List. And there must have been well known wonders in places Alexander never had time to conquer. Over the centuries, as the number of notable sights has multiplied, the tradition of holding to a specific limit has become ever sillier. Yet, curiously, we continue to accept such lists—like my mother’s—at face value and to grant authority to their usually anonymous creators.

Under such circumstances, the longevity of the list of wonders tradition is remarkable. Despite the fact that the original list ceased to have any usefulness after only a few hundred years—owing to the rapid disappearance of almost all the Wonders—it has remained so famous as to be essentially common knowledge. It continues to be the subject of new books and to inspire modern versions like my mother’s. The tourist who embraces an anointed list of wonders—or a 3-star guidebook line-up—must be responding to some long-standing, basic need. Not only was my mother not alone, she seemed to be in company with the better part of the human race.

Just how seriously did my mother take the List? Did she really expect to visit the places she had missed? Was her holding onto the List about pride—or hope? Or, rather, was it a brave stand in old age against the finite nature of her traveling days? Unanswerable questions, all. Even if she were here to respond, my questions would have made no sense to her. “It’s just a list! Why do you make such a big deal about everything?” This discussion would not have appealed to her in the least.

If we forgive the foolishness of wonders lists, it is because we recognize a common chord. Who is not vulnerable to the alluring assumption that it is possible to distill a world of sights to nothing but the best and to a manageable number at that? Perhaps travel’s exchange of the familiar for the unknown makes us particularly susceptible to a promise of order in an impossibly disorderly world. Or perhaps we acquiesce to the list’s implicit conviction out of a deep wish, in the face of an impossible task, to have someone else do the choosing. From the beginning of tourism to the present, lists of wonders have enticed travelers with an irresistible come-on: reduce the vast possibilities in a world of wonders to a magic number and grasp the cornucopia of life.

In the face of dizzying choices and a frustrating limit to what can be done, seen, or known, the List of Wonders holds out the promise of making the most of our allotted time. Reassurance in the form of a checklist. A measure of the immeasurable. A futile but valiant quest. Mixing reason and irrationality, my mother nurtured, in all things, the illusion of order. So do we all to some degree and in our own particular ways. I wonder, is the effort to grasp the elusive identity of a parent so very different?

Leave a Reply