I’d been happily married for 46 years, and yet my heart still raced whenever my college boyfriend crossed my mind. We hadn’t been in touch since the affair ended without grief, when Ernst graduated and returned to Germany. But when my husband Michael and I decided to visit Berlin, the thought of seeing Ernst again, of exploring those persistent, swept-away feelings, became irresistible. Despite the risk.

Michael, a nostalgic, loves the idea of revisiting the past and is not a worrier. To him, a bygone love could have nothing on our wonderful life together. I had the misgivings.

I knew how charged my memories were. Ernst’s craggy face and lanky frame were the epitome of European sexiness to me. He seemed so German, you’d never have guessed he’d grown up in the States. And herein lay his transgressive appeal: he’d been utterly unacceptable to my parents who—like many Jews in those days—hated everything German.

It was dizzying enough to be in the academic Eden of Bryn Mawr and finally free from my parents’ critical surveillance, without also being in love—and a taboo love at that. On nights I had to study, Ernst scaled the stone wall of my gothic dorm (where men weren’t allowed), climbing into my room through the casement window. Only the Juliet balcony was missing.

With that bliss came terror. The first summer of our romance, I discovered I was pregnant, and the illegal abortion Ernst arranged from abroad was discovered by my parents. Insisting I give him up for a year, they only stoked the longing. The second summer of our relationship, the ban not quite over, I traveled to my college’s outpost in France, where Ernst secretly met me in his new, red convertible, and off we fled. I tied up my long hair in a houndstooth scarf and felt like Audrey Hepburn.

Our whole romance felt like a movie—and was as artificially framed. Ernst and I floated on a cloud of blissed-out mutual adoration. We never discussed our families, our courses, the future. I studied French and Italian, never once considering German. If the romance had an implicit expiration date, we ignored it. Then, though I’d pined throughout our forced separation, when Ernst returned to Germany for good, I was fine. It was as though an addictive TV series had simply come to an end. In fact, I’ve repressed all memory of his leaving. Did we even say good-by?

Three years later, I fell head over heels for Michael, a handsome, Jewish New Yorker who shared all my fascinations. My parents, whom by then I was less interested in torturing, exhaled.

Yet, a lifetime with Michael—of joys savored and struggles overcome, of a family built and lessons learned, of joint passions and memories amassed—failed to dislodge Ernst from my nervous system.

After decades of silence, calling Ernst wasn’t easy, but the moment was electric. Instantly, I was 17, feeling the full force of those long-ago yearnings. His accent, a portal into the past, made my heart pound—and the way he said my name, “Leez.” We took up where we’d left off and could have been speaking on dorm phones. But at the same time, I remained the observing 65-year-old, hearing a voice that, after a half century of smoking, sounded its actual age.

Visiting Ernst meant detouring to Munich, but Michael was happy to indulge me and curious, himself. As the reunion neared, my anxieties multiplied: What did I mean to him? Would he recognize me? Would I be undone by the old feelings?

My mind was churning. When I called to confirm his address, the night before our date, Ernst and his wife were already in bed; she answered and passed him the phone. Later, I dreamed the four of us were in bed together, Ernst and I on the outside, talking to one another over our sleeping spouses. Then, suddenly the dream changed, and I was searching for my lost dog, Baby, our current family whippet. “Baby, Baby,” I cried frantically, wracked with sorrow—my very first awareness of grief over my long-ago abortion.

The next evening, Michael and I took a taxi to Ernst’s house in a surprisingly pastoral setting outside the city. His lovely wife greeted us at their front door, accompanied by their youngest daughter who, at 23, was older than I when I’d last seen her father. And then, there he was, back-lit by the setting sun and just the same: still blond and lanky, as handsome to me in his 60s as he’d been in his teens, the young boy still visible in the now much craggier face.

I hadn’t dreamed our romance; we occupied the same place in each other’s old-love memory bank. We’d barely got past hellos, when he showed me the gold chain I’d given him all those years ago, which he still wore. He welcomed Michael, poured champagne and rushed to show us his life: the house he’d built, his recreated college library, a photo of him surrounded by his radiant wife and daughters. It was spell-binding, like finding a gripping novel I’d misplaced and speed-reading through the high points.

The three of us relocated to a nearby restaurant, where I quickly realized I’d only partly understood what had drawn me to him. Yes, I’d been turned on by his European allure, his being forbidden, and sticking it to my parents. But equally irresistible were his passionate nature and appreciation for me! At dinner he asked Michael’s permission to hold my hand and repeatedly told me I was beautiful. At the peak of adolescent insecurity, I suddenly realized, Ernst had given me the gift of seeing me as I’d most wished to be seen.

Curiously, I felt free to ask him absolutely anything. It was as though our connection was for life and gave me the prerogative. Despite the passage of time, of our entire adult lives, in fact, I felt I understood him to the core. And I don’t think it was a fantasy. We knew each other intimately as we were at a special, peak moment: a chrysalis version of ourselves that carried the imprint of our pasts and futures.

Which may be why nothing I learned at dinner seemed surprising. He told us his wife keeps him alive despite his fast-living (and sweetly asked Michael if I do the same for him). While Michael and I roam museums, Ernst parties on the Riviera. Our lives are so different; if we hadn’t been teenaged lovers, we’d likely never be friends today.

Meeting Ernst again brought such a maelstrom of sensations I could barely take them in. But I was conscious that my initial experience on the phone with him—of being in two time zones of my life simultaneously—did not recur, when we were actually together. His physical presence, his vitality, facial expressions, his adult particularity, temporarily blocked my mesmerizing memory of him. In the present with him, I felt none of the old charge.

Much later, I realized that ours was a shipboard romance that was over by the time we’d pulled into shore. Underneath, we’d always known our intoxicating differences spelled doom, that the romance couldn’t survive real life. Still, for a trial run, its impact was deep and lasting—and left me hopeful about love.

We remember best what we feel most intensely. No wonder first love memories remain vivid, their ecstasy owing much to their being first and outside real life.

I’ll always be in love with the boy that Ernst was. And why not? It threatens nothing that’s come after.

First published in a shorter form, Valentine's Day, February 14, 21018 on Cognoscenti at wbur.org/cognoscenti

Your husband is a real spirt, Elizabeth! He must be a very secure human being. Ernst’s wife as well must be very secure and a sport.

For an essay about love; love.

A charming picture window you’ve opened up into your past. And present! I’ve loved reading this.

Thanks so much!

am not sure how this works. see my note above.

and my website below if you like.

Hi Liz U were lucky then and

U r lucky now! ImAgine falling in love twice

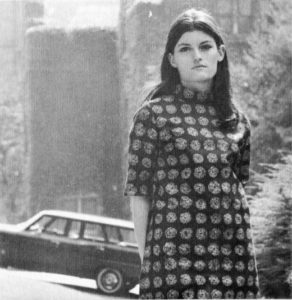

Your picture looks like u r just waiting for your MomandDad to disown u

Your boyfriend looks like a handsome bad boy! Michael is amazing to do this with u

What a poignantly beautiful story!

As Cole Porter said

“We’d have been aware that our love affair

Was too hot not to cool down”

Your courage in exposing that much of your history and feelings is admirable, courageous, and show a real dedication to the art of writing. It is why I like art so much better than reality, even when “based on our memories of reality. ” Thank you for sharing. It will inspire me to remember.

Thank you, my friend.

Oh Elizabeth, this is a wonderful, beautiful story. A fairy tale really. I, of course, am thinking about my own too. Mine was a quieter romance and reunion, but has haunted me the same way, and still does.

So wonderful to hear it resonated.

Having heard a version of this from you, it is even more compelling in written form. It is so evocative and allows the reader to reunite their own feelings of first love to your lovely story.

Once again, thank you for a gem. You and Michael are so brave and wise. Your writing about your life/loves together always moves me.

Delicious, and poignant. Beautifully written.

what a wonderful, poignant and revealing story! and one i was surprised by, having known much of your history during our long friendship. you are fortunate, indeed, to have had this experience, and it is testimony to your never-ending curiosity that you pursued a recent reunion. and affirming that it left you the way it ought to have, it seems to me – regretting nothing and appreciating much.

I can’t say how much I appreciate your connecting through this story. You do know me, I feel, and it is wonderful to be known by you, truly wonderful.

Such a tender first love story, with the lost baby a tragic undercurrent that deserves its own place in your oeuvre. Michael is definitely the real thing!

What a lovely response, Sara, and how wonderful to hear your voice.

Your vivid true life tale holds so much hope for honest reconnection with past history. Such risk and such success–thanks for your excellent skill in sharing this story.

What a lovely take on the story! Thanks so much, Lisa.