Eduardo Porter, who describes himself as “the son of a tallish, white father from Chicago and a short, brown Mexican mother of European and Indian blood, wrote in the NY Times (Aug 11, 2008) about how differently race is viewed in Mexico, where he grew up, than in the USA. According to him:

“Today the Mexican census doesn’t ask about race and only started asking about indigenous ethnicity in 2000. Jose Vasconcelos, a politician and philosopher, wrote in the 1920’s that Mexicans were of the ‘cosmic race’ — that which included all others. Yet Mexico’s state-sanctioned mestizo identity allowed its rulers to ignore its beleaguered indigenous populations — virtually defining them out of existence.”

In contrast, American politics are so racially sensitive “whether they resulted in Jim Crow laws or affirmative action,” that we cannot even imagine not categorizing people into racial groups. Porter sees positive and negative effects from our racial sensitivity: on the one hand, there is a well-publicized awareness of racial inequality; on the other hand, an acceptance of the natural, ongoing blending is thwarted. There continues to be a huge disparity between what genetic testing shows about our identities and the way we identify ourselves on census questionnaires.

Porter explains the Mexican take on race as having evolved from the promoting of a “mixed Mexican identity as a way to merge Europeans and pre-Columbian nations into a modern Mexican state.” I wonder if that covers it.

The Spanish who settled Mexico had different attitude about race and racial mixing from those of the northern Europeans who settled New England. The Spanish interbred with both the Indians of Mexico and of California. Why did the English and other Northern European colonists interbreed with their African slaves but not with American Indians? It is something of a mystery.

Was it because the New Englanders arrived as colonizers—with wives—not as conquerors? Was it because they never enslaved the Indians as did the Spaniards? Or was it a cultural difference between Northern and Southern Europeans?

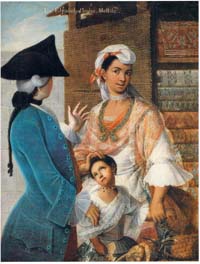

From the beginning in Mexico, light-skinned progeny of mixed race couples had a place in society, whereas in the USA any African blood consigned the descendent to outcast status.

There just seems to have been more racial mixing and more tolerance for it in Mexico. In fact, there may have never been laws in Mexico prohibiting intermarriage. According to the Redbones Heritage Foundation website: “1514 Spanish law of 19 October explicitly permits intermarriage with Indians; permission of intermarriages reenacted in 1515 and 1556; intermarriage with blacks neither encouraged nor prohibited.” Whereas, as early as 1630 in Virginia anti-misogyny strictures were recorded — and more specifically: the “1638 Ordinance of the Director and Council of New Netherland prohibits adulterous intercourse between whites and heathens, blacks or other persons, upon threat of exemplary punishment of the white party.”

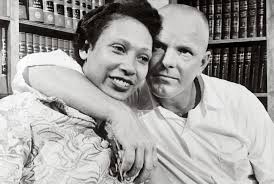

Something was different from the very beginning. And it remained different. Laws against intermarriage were not declared unconstitutional in the USA until 1967, in the case of Loving versus Virginia.

The release of a movie on the Lovings in 2017 stimulated more investigation and reporting. It turns out that Mildred Loving identified as Indian, not black, as reported in Time Magazine, adding a new twist to the story.

Americans’ pride in their identity as a melting pot is completely at odds with their struggle to accept racial intermarriage. The Mexican view of race is proof that our problem with race need not have evolved as it did. But perhaps things are slowly changing.

The New York Times ran an interesting article, January 14, 2012, concerning the Latino inclination to reject race as an identity in favor of culture. Many feel that the racial mix of their ancestry is just too complex to categorize. Furthermore, their sense of identity comes from a shared language and immigration status, not from skin color, which varies extensively. Many light-skinned Hispanics, viewed as non-white here, identify as white since they come from countries where they were considered white. Black Hispanics, on the other hand, may reject the identification as Blacks with whom they do not share a common culture. Although there are 15 choices of race on the last census, more than a third of Latinos chose “other.” Really, this is a problem only for political groups, who naturally want the highest numbers they can get so as to maximize their influence.

It’s easy to see that this disinclination to identify through race is the wave of the future. Racial mixing will continue until everyone will be desensitized to it, and we will look back on this concern as a relic of the past. All that remains to be seen is how long will it take.

Leave a Reply