It is generally held that the road to mastering internal conflict winds through our past and back to the conflict’s source. As children, we do our best to make sense of what feels wrong, with whatever limited understanding we have at that moment. And so we often come to false conclusions–most commonly that we were responsible for things that were in fact entirely out of our control. We then carry these mistaken ideas through life, without questioning them. By revisiting our childhoods, we may be able to identify these misconceptions and to correct them in the light of our adult understanding. But getting to these critical memories isn’t always easy.

As a memoir-writer, I spend a lot of my time riffling through the past, and I know how elusive the potent details can be. Putting aside the issue of the mutability and subjectivity of memory, it is the emotion of past moments, not the literalness of particular facts, that is the subject here. We may conflate a repeated event into a single memory of it, but how it made us feel or what we thought at that time is what is most telling, meaningful, and often hard to recall. After all, we don’t walk around with our heads full of vivid memories. We pack them away so that we can move forward in our lives. Moreover, we may want to ignore what was painful or uncomfortable. We may even forget having locked up certain memories altogether. But the time may come when you need them—for memoir-writing or self-understanding.

What is forgotten, though, isn’t gone. Our missing memories are locked somewhere in our brains; we just have to find our way to them. All sorts of chance things can trigger memories to break through. For the writer Proust, it was famously the taste of a madeleine cookie dipped into linden tea. It could be a phrase of music or a voice. But if you want actively to pursue the past, you can’t leave it to chance; you have to provide the trigger yourself.

The magic key that works for me and may work for you is the right photo. I learned this trick from a psychiatrist I used to see, and I find it powerfully effective. The “right” photo is one that you sense has potency, one in which there is something behind your polite or empty smile. If you spend a lot of time peering at such a photograph of yourself, you will find that you can connect with the state of mind of that earlier-you. You can recognize through the expression and body language of your-then-self how you were feeling, if not literally at that exact moment, then generally at that time in your life. And with that connection to your earlier self can come your whole early world, in living color.

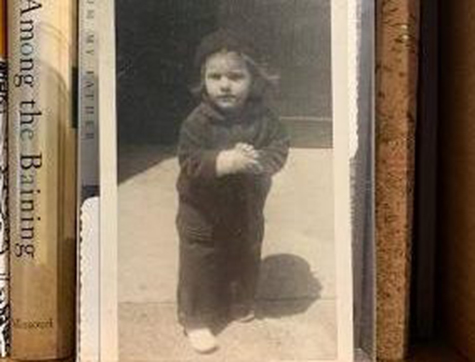

Here is an example.

When I first looked at the picture that accompanies this essay, I saw only my curious expression. But after a while, I could see my confusion and anxiety: the furrowed brow, the clenched hands, the searching expression. I kept the photo on a shelf above my desk, where it reminded me of just how old that confusion was. And the more I looked, the more I could see into the mind of the beleaguered child and the more sympathy I felt for her. I could sense in my child-self the familiar awareness of some hovering, parental expectation and of my compulsion to try to satisfy it. The thought, “What do they want from me?” hadn’t yet formed in my mind, but it was starting to coalesce. It wasn’t until adolescence that I became conscious of this high bar and of my chronic failure to meet it: I wasn’t neat; I couldn’t spell; I wasn’t musical. Seeing the early precursor to my lifelong fear of not pleasing my parents brought the realization that their concern about my not measuring up predated all my failures. The problem was not with me but with them.

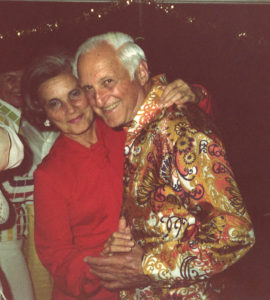

And here’s another example.

Photos can also reset a view of the important people in your life, which can lead you to question the why of your misunderstanding. My parents fought like the proverbial cats and dogs: continuously and as though their lives were at stake. They agreed about everything: friends, money, politics, all the things couples normally fight about. Instead they limited themselves to battling about complete irrelevancies. l wrote that their fighting was a pure thing, like zen archery. They fought about the address of a long-closed shoe store, who had won the couples championship years earlier, with whom they were having dinner the night a certain joke was told, the pronunciation of a word. Their fury over these disputes led me to think that their marriage was unhappy.

Later, pouring through old photos after their deaths, I saw dozens of images of them dancing or dining or just gazing out at a distant view in which their harmony and pleasure at being together was obvious. How could I have failed to see this when they were alive? Did I want to be fooled by the fighting? And what was this fighting really all about? A whole new inquiry opened up at this realization.

Later, pouring through old photos after their deaths, I saw dozens of images of them dancing or dining or just gazing out at a distant view in which their harmony and pleasure at being together was obvious. How could I have failed to see this when they were alive? Did I want to be fooled by the fighting? And what was this fighting really all about? A whole new inquiry opened up at this realization.

Old photos are precious relics. They are the primary source material of your life. Let them take you back to before you were born and to the emotion-packed moments between then and now. Be open to being surprised. Be open to being corrected. You may find that what you have been failing to see is the very thing that sets you free.

Liz, yours are some amazing insights.

Who knew … I’ve seen these issues in my photos as well. Thank you for sharing.

Your write eloquently and with deep insight. It is a pleasure to learn from your reflections.