To most, the sixties “generation gap” was a vague, pop-culture generality. To us—my parents on one side, my husband Michael and I on the other—it was my family’s defining motif. We were deeply, truly, madly split on every subject. Police brutality. Dean Martin. Grey Poupon versus French’s. It was all equally significant. Where you stood on thank-you-notes said as much about you as where you stood on Malcolm X. In fact—and here we actually agreed—it said exactly the same thing. You could deconstruct any difference of opinion and get to core values in a heartbeat.

But no issue drew a line-in-the-sand more than our differing travel styles. My parents preferred to see the world from deep within a pre-arranged bubble of 5-star comfort and security. And they were after 5-star sights; if something wasn’t listed as a must-see, in their opinion, there was a damn good reason. For Michael and me, breaking out of the bubble was the whole point. And what we sought was the obscure, the sense of going “beyond.” A tour? Sheep herding.

Underlying our divergent preferences wasn’t just the forty-year age difference; it was divergent self-images. My parents saw themselves as discriminating travelers. They proudly carried their quality standards like a regimental banner and made uncompromising judgments about cleanliness, punctuality, and the thread count of linens wherever they went. Their hard work and success had earned them the right. We, direct beneficiaries of all that hard work, naturally rejected their values. In fact, we felt obliged to prove we didn’t need any of the creature comforts they regarded as the hallmarks of civilization. We wanted to be good travelers—flexible, tolerant, hardy, in short, virtuous—and were fervently committed to appreciating everything, no matter what. They were a visiting accreditation team, we a couple of earnest scouts.

Not surprisingly, traveling together on our annual foray from my parents’ winter home in Ajijic, Mexico was not a piece of cake. Yet we refused to be daunted by experience. Optimistic to the bone, we fully expected each journey to demonstrate our family’s capacity for generational harmony. Of course, it didn’t hurt that there were 355 days between trips—just enough time for hope to triumph over history.

A trip on Mexico’s scenic Copper Canyon railroad, when Edna and Leo were in their early 80’s, was my suggestion. The train ride itself had plenty to recommend it: one of the greatest railway engineering feats of all time, it traversed the most rugged and spectacular scenery in northwest Mexico. True, the departure times seemed vague, the photos a little out-of-date, but our brochure described an elegant train with dining car, “360-degree glass dome and bilingual guides.” Perfect for my parents, avid train travel enthusiasts, who loved to reminisce about eating fresh caviar straight from the tin with a spoon on the Trans-Siberian Railroad. Our excursion required an overnight stay at each end of the line in remote, provincial towns, but I was sure my parents were up to it.

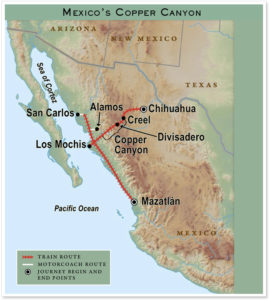

Increasing the challenge slightly, Michael and I argued for  getting off the train mid-way to spend a couple of days visiting the canyon area. In those days, most tourists just rode the train from Los Mochis, on the coast, to Chihuahua, twelve hours inland, and, to be honest, for Michael and me this was reason enough to get off. But we were also enticed by the fact that the region’s network of canyons and unassimilated Tarahumara Indian population had been virtually unknown until the railroad’s completion 30 years earlier.

getting off the train mid-way to spend a couple of days visiting the canyon area. In those days, most tourists just rode the train from Los Mochis, on the coast, to Chihuahua, twelve hours inland, and, to be honest, for Michael and me this was reason enough to get off. But we were also enticed by the fact that the region’s network of canyons and unassimilated Tarahumara Indian population had been virtually unknown until the railroad’s completion 30 years earlier.

I spoke to the manager of an American-owned inn that called itself a “1st class rustic hotel,” located at about the halfway point. It sounded perfect: comfort for them, atmosphere for us. If they didn’t want to come for nature walks, my New York sophisticate parents could relax on the porch rockers and soak up the ambiance. As an opportunity for isolated togetherness—something we had never previously come close to enjoying—it looked unparalleled. “If there’s a hard way to do something, you’ll find it,” they said. But they let us persuade them.

* * * * *

Our launching was not auspicious. We arrived at night in Los Mochis to find that our motel was not just no-star; it was something from a 50’s film noir: cracked linoleum, torn window shades, mix-matched furniture. How did we know there weren’t bedbugs, Leo wanted to know. Then we learned that our 8:00 A.M. train was actually leaving before dawn, at 4:00, “an “unspeakable” hour,” according to my mother. Jared and Zoë were thrilled at the prospect of getting up in the dark, and I pointed out the bright side—less time in our sleazy motel—but Edna and Leo didn’t appear to take much comfort from my cheery words. Climbing into a broken down taxi a few hours later, rumpled and bleary-eyed, they announced they had survived the night by sleeping on top of the bed in their clothes.

At the station, my mother mustered what good humor she could, but my father, something of a curmudgeon in the best of times, saw no reason to bother. The train and our vision of it were on two completely different tracks. Not only was the real thing not the plush one of the brochure, it was ancient and dilapidated. No glass dome. No guides. As the sun rose, we could see the windows weren’t just not clean; they were completely opaque with dirt, a serious hindrance to sightseeing.

At the station, my mother mustered what good humor she could, but my father, something of a curmudgeon in the best of times, saw no reason to bother. The train and our vision of it were on two completely different tracks. Not only was the real thing not the plush one of the brochure, it was ancient and dilapidated. No glass dome. No guides. As the sun rose, we could see the windows weren’t just not clean; they were completely opaque with dirt, a serious hindrance to sightseeing.

Initially no one complained. My father, who’d decided his only salvation lay in a book, wasn’t picking his head up in any case. Michael and I chose to see the train’s decrepitude as atmospheric patina, while Jared and Zoë—ten and eleven and traveling the rails for the first time—were thrilled to discover there were no seat belts; they could walk around as they hurtled through space. And for a few hours my mother’s delight in their excitement seemed to distract her. Staying upbeat took effort, and she worked at it heroically.

But at 7:30 A.M. a meal—the only meal of the daylong trip—arrived in a Styrofoam box. My mother lifted the lid, eyed the sliced gray meat on buttered rolls, the dubious macaroni salad, and oddly foamy custard, and gasped with horror. “They’re kidding. They must be kidding!” It was the straw that broke her attempt at resilience. For the rest of the ride, like my father, she gritted her teeth and gripped her book as though for dear life. The two—who, under normal circumstances, fought from morning to night—were united in their disapproval. If there was something to view, they didn’t care. “We’ve seen scenery,” was how they put it, glowering.

Michael and I, meanwhile, were reveling in the sights they were missing. True, we had to lower one of the windows or stand between the cars to see it—but we didn’t mind. If anything, the inconvenience added to our pleasure; it made us feel more in sync with the rugged landscape. Except for an occasional power line, this was pure John Wayne country: wide vistas of flat prairie, cactus, an occasional horse-drawn cart. Narrowing our eyes in the gritty wind gave us what felt like a flinty, chiseled look; standing outside on the dusty platform, we rolled with the lurches, only one short step from actually riding the range. After a few hours we entered a deep, semi-tropical cavern that sprouted air  plants from the cracks in its sheer walls. We traversed enormous tunnels, made complex switchbacks up the mountains and crossed suspension bridges so high that hawks soared far below us. We were enthralled—and entirely unperturbed by my parents’ negativity.

plants from the cracks in its sheer walls. We traversed enormous tunnels, made complex switchbacks up the mountains and crossed suspension bridges so high that hawks soared far below us. We were enthralled—and entirely unperturbed by my parents’ negativity.

Where was our guilt? Had we talked some friends into a trip they weren’t enjoying, we would have been anguished. But, as it was my parents, we were impervious. Over the years we had inured ourselves to their frequent bouts of outrage and had cultivated a measure of detachment as a prerequisite to traveling with them. It wasn’t difficult. My parents may have been in their 80’s, but they were hardly vulnerable old folk. They were a dynamic duo who disdained victimhood. Infinitely resourceful, they habitually turned disappointment into a feeling they could enjoy: indignation. They loved to complain. In fact, they may have gotten as much pleasure from the many trips they hated as they did from the ones that worked out.

At El Divisadero, the train stopped so everyone could get down to see the natural lookout over the gorge of the Rio Urique. The Copper Canyon Rail Tour was misnamed: the canyon could only be seen from this one stop, and even there, it wasn’t visible from the train itself. The gorge is touted as ”four times the size of the Grand Canyon and 1-1/2 times as deep,” but such statistics intentionally miss the point: it is considerably less beautiful. Instead of a vast ravine of pink-to-coral-to-plum striated rock walls dropping vertically as far as the eye could see, we looked out at what seemed to be little more than a large mountain range covered in dry vegetation. Michael and I didn’t care. We focused on the positive: the pleasure of stretching our legs on terra firma, the charm of the Indian girls selling their simple dolls and baskets by the side of the lookout path. My parents, however, were incensed. “They compare THIS to the Grand Canyon? They ought to be sued!”

An hour later, we arrived at dusty outpost of Creel and were met and driven to our hotel, a long log building with a pitched tin roof and continuous open veranda. A pig and two roosters ambled in front of the wide central stair leading up to the entrance. Edna and Leo seemed not to be immediately taken with the hotel’s charm. But I was in heaven. The  rooms, opening directly onto the porch, had varnished log and wattle walls, tile floors, and dark plank ceilings. Each was heated by its own wood stove and was lit by glass kerosene lamps. The whole place had a fabulous Wild West aura. Turning their backs on the rockers and the view, my parents retired to rest until dinner, while we eagerly set out with the kids on a hike to a nearby waterfall.

rooms, opening directly onto the porch, had varnished log and wattle walls, tile floors, and dark plank ceilings. Each was heated by its own wood stove and was lit by glass kerosene lamps. The whole place had a fabulous Wild West aura. Turning their backs on the rockers and the view, my parents retired to rest until dinner, while we eagerly set out with the kids on a hike to a nearby waterfall.

The evening meal was served in the central dining room, a stucco-walled room framed by a huge stone-studded arch. Tall mission-style chairs with leather seats and backs had been arranged around three long refectory tables placed in an open ”C.” Kerosene flames in heavy wrought-iron lamps cast the whole room in a deep atmospheric glow, the flickering light reflecting off the enormous spherical water jugs. Every detail showed the great care that had gone into creating this romantic Sierra Madre hide-away. Surely my madre was impressed. “It’s so beautiful, it takes your breath away, doesn’t it?” I whispered to my mother. If it did, I never found out; it seemed to have taken her voice.

In fact, both she and my father were uncharacteristically quiet at dinner. The other guests were an interesting mix of Mexicans and Americans, just the sort of people my ordinarily out-going parents loved chatting up. The meal was served family style, and Michael and I and the children enjoyed it. But then, unlike our elders, who managed to live part-time in Central Mexico while avoiding the local cuisine, we like Mexican food. Cheerily oblivious to the end, I asked my father, hunched over and mumbling to himself, what he thought of the meal. “If I could see it, I might be able to tell you,” he shot back.

The next morning, over fresh orange juice and heuvos mexicanos, my parents lowered the boom: they were leaving. They were taking the next train out—that very afternoon. It was so dark at night they couldn’t read. They could barely find their way around their room; the icy floors were giving them chilblains. They couldn’t stand the smell of kerosene. “We’ll wait for you in Chihuahua,” they said. “It can’t be worse than this place.”

We spent the morning together touring the area by car. Even  in anticipation of imminent escape, my parents seemed only slightly less glum. They were not enchanted with the surreal moonscape of bizarre, eroded rock formations, jutting up like giant mushrooms. They were not intrigued by the cave-dwelling Indians who welcomed us into their surprisingly cozy winter apartment scooped out of the side of a cliff. Edna and Leo were not taking any chances: they left for the train, good and early.

in anticipation of imminent escape, my parents seemed only slightly less glum. They were not enchanted with the surreal moonscape of bizarre, eroded rock formations, jutting up like giant mushrooms. They were not intrigued by the cave-dwelling Indians who welcomed us into their surprisingly cozy winter apartment scooped out of the side of a cliff. Edna and Leo were not taking any chances: they left for the train, good and early.

Our first reaction was relief. Now we could get into some serious sightseeing. We arranged to take a horseback excursion that afternoon to a centuries old Tarahumara church.

But our stalwart-travelers image came under attack almost immediately. The horses turned out to be seriously bedraggled creatures, bags of bones with worn-out, patched-up saddles. The two guides—horseless themselves—intended to follow on foot. We tried to argue that with such an arrangement we could go no faster than the men could walk, but, once mounted, we understood: the horses would only move if the men drove them on with a stick. With the kids’ steady wail of empathy for the poor animals, our resources of positive-thinking gave out. I tried to start up one of the old camp songs we revived on long car trips, but no one joined in, and I soon gave up. We rode on silently across a thickly forested, monotonous, rocky terrain that increasingly seemed like the Slough of Despond in Pilgrim’s Progress. The obvious poverty of the region was suddenly overwhelmingly depressing. The excursion had just begun, but we couldn’t wait for it to be over.

Finally we arrived at the church: a simple structure. It didn’t look like much. Three pigs were rooting in the dirt outside. The interior was plainly painted and empty, since the Indians prefer to sit on the floor. My parents would not have been impressed. I could hear their classic response: “They dragged us all the way out here to see this!”

But just imagining their words seemed to increase the church’s austere beauty. Seen from the right vantage point, in the quiet of the moment, in its dusty pastel setting, the place had a certain poetic otherworldliness. It began to dawn on me: our previous enthusiasm may have owed something to my parents’ lack of it.

At dinner that night I got another rude awakening. Turning to my new neighbor at table, I asked how long he was staying at the hotel. He and a companion were leaving the next day, he said, on a hiking trip down 4000 feet to the bottom of the canyon where there was an old silver mine and the ruins of a hacienda. He hadn’t finished his sentence before my notion of having traveled to the “back of beyond” had shriveled like a leaky balloon. The Lodge at Creel, which seemed so remote to me, was only the beginning of their journey; my “beyond” was my neighbor’s home base.

Coming on the heels of our afternoon equestrian adventure, it was clear that this lesson in relativism applied not just to distance. My family’s two supposedly character-defining modes of travel were looking less black and white with each passing minute. We may have been hotshot travelers in relation to my octogenarian parents; but in relation to the hikers we were marshmallows. Not only was the line-in-the-sand less fixed than I’d imagined, but my position on one side seemed to depend on who happened to be on the other.

Most shocking was the realization that if our rosy take owed something to my parents’ bleaker view, the reverse was probably true: our monopoly on virtue may well have made the floors seem colder to my parents, the room darker. Had my relentless good cheer pushed them over the edge? When they took off for Chihuahua, had Edna and Leo been fleeing more than the smell of kerosene?

When we were reunited in the provincial capital a day later, we found the tables turned. Having familiarized themselves with Chihuahua, my parents acted as though they owned the place and were surprisingly enthusiastic about what struck us as a grim, down-at-the-heels town. They were charmed by our seedy hotel—”so evocative, so picturesque”—though our dank rooms looked into an air shaft, and the sounds of the marimba player in the lobby wafted up to us at all hours of the day and night. They’d already made a complete tour of the town but were happy to revisit the sights, especially  Pancho Villa’s house, where in the courtyard stood the very car in which he was assassinated. They couldn’t wait to take us to their favorite restaurant, where we had to try the completely unremarkable Caesar salad they insisted was the best they’d had anywhere in the world. We ate without much gusto, picking at our food, but they didn’t seem to notice. While we were glad they’d found something on the trip to enjoy, whatever it was they saw in Chihuahua was beyond us. In the end, there was only one thing we could see clearly: to feel like true travelers, it helps to have a couple of touristic sight-seekers in tow, the older and grouchier the better.

Pancho Villa’s house, where in the courtyard stood the very car in which he was assassinated. They couldn’t wait to take us to their favorite restaurant, where we had to try the completely unremarkable Caesar salad they insisted was the best they’d had anywhere in the world. We ate without much gusto, picking at our food, but they didn’t seem to notice. While we were glad they’d found something on the trip to enjoy, whatever it was they saw in Chihuahua was beyond us. In the end, there was only one thing we could see clearly: to feel like true travelers, it helps to have a couple of touristic sight-seekers in tow, the older and grouchier the better.

first published as "Travel Wars" in The Unsavory Traveler, Seal Press, Canada, 2001

Wonderful descriptions! I felt like I was right there with you. Your writing is inspiring me.

So insightful, Liz! It rekindled memories of my own parents, who were incurable romantics rather than curmudgeons, but they also briefly focused on that region of Mexico as a retirement location. My father was a “railroad nut” and I have his narrative of that same Copper Canyon trip which I plan to dig out now! They actually wintered in Ajijic for a couple of years, but in a self-renovated van, not a posada. My father was a reluctantly retired college professor with more ingenuity than money. My mother “bloomed where planted” and cheerfully rinsed her local veggies in chlorinated water and put wildflowers on the picnic table. Travel was their antidote to depression and the constant anxiety of financial stress, their reward for getting three children through college and out of the house. You have given me much to think about, and a fresh approach to examining my own family dynamics.

Great story, Elizabeth! I remember you talking about this trip many years ago but this essay reminds me how easy it is for our perspective to change depending on circumstances. Loved this.

Finally, I have read this wonderful essay. You capture the eternal conflict of being with parents, the essential feel and look and beauty of rural Mexico. This is all written in a discriptive,, humorous maner. A pleasur to read.